Advisor Compliance and the Madoff whistle-blower’s book: ‘No One Would Listen’ by Harry Markopolos

More light has been shed on the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme with the publication of “No One Would Listen.” This book focuses it’s ire on the SEC who completely missed the Madoff Ponzi despite being warned in advance and in time to prevent billions of dollars in losses.

More light has been shed on the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme with the publication of “No One Would Listen.” This book focuses it’s ire on the SEC who completely missed the Madoff Ponzi despite being warned in advance and in time to prevent billions of dollars in losses.

This writer agreed with Harry Markopolos’s conclusion that “we shouldn’t trust the government.”

Writes Andrew Fitzgerald:

My wife had the Today Show on this morning to which I usually don’t pay any attention, but Matt Lauer was interviewing Harry Markopolos who I had seen interviewed before on Frontline. Markopolos was a competing trader tasked with figuring out Madoff’s secret to such great returns. He said that he conclusively determined his operation to be a fraud in 30 minutes and over the next several years informed the SEC four separate times. He said that the big problem with the SEC was that they’re staffed with lawyers who don’t know anything about money and investigating. I remember in the Frontline piece he said that it would have been easy enough for the SEC to contact every broker on the NYSE and find that none had ever placed a trade for Madoff.

The great parts of his interview this morning were when Lauer questioned him about his fears of being threatened by Madoff. Markopolos said that he bought a gun and if he were personally threatened by Madoff he planned to kill him since, “it was either him or me.” Lauer looks at him quizzically asking how he would explain that to law enforcement. Markopolos, who doesn’t exactly look like a Charles Bronson vigilante, said “well I’d hope not to get caught. I certainly had some good Army training, and it was really him or me. I had a family to protect. The government wasn’t protecting me; they were not doing their jobs, and I felt forced into a rather difficult moral dilemma.” Lauer ends the interview by asking him what lessons should investors learn from this mess. He answers, “don’t trust your government.”

I felt the whole interview had a great libertarian ring to it, with our government budget going to no good purpose except possibly training a would-be vigilante and the regulatory agency being warned repeatedly about the greatest private fraud in American history to no effect. Source: http://www.lewrockwell.com/blog/lewrw/archives/52150.html

You can see Harry Markopolos interviewed on this 8 minute segment from yesterday’s Today Show.

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

Here’s a book excerpt from the Today Show’s website:

Harry Markopolos on investigating one of the biggest frauds in history

TODAY books, updated 7:01 a.m. PT, Mon., March. 1, 2010

Harry Markopolos is the whistle-blower who uncovered Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme 10 years before the rest of the world learned of the biggest financial crime in history. While a lot has been written about Madoff’s scam, few actually know the dramatic details of how Markopolos and a small group of sleuths went about investigating the fraud that reached around the globe. In “No One Would Listen,” Markopolos shares his story. An excerpt.

On the morning of December 11, 2008, a New York real estate developer on a JetBlue flight from New York to Los Angeles was watching CNBC on the small seat-back television. A crawl across the bottom of the screen reported that Bernard Madoff, a legendary Wall Street figure and the former chairman of NASDAQ had been arrested for running the largest Ponzi scheme in history. The developer sat silently for several seconds, absorbing that news. No, that couldn’t be right, he thought, but the message streamed across the screen again. Turning to his wife, he said that he knew that she wasn’t going to believe what he was about to tell her, but apparently Bernie Madoff was a crook and the millions of dollars that they had invested with him were lost. He was right — she didn’t believe him. Instead, she waved off the thought. “That’s not possible,” she said, and returned to the magazine she was reading.

The stunned developer stood up and walked to the rear of the plane, where the flight attendants had gathered in the galley. “Excuse me,” he said politely, “but I’m going to be leaving now. So would you please open the door for me? And don’t worry — I won’t need a parachute.”

At about 5:15 that December afternoon, I was at the local dojo in my small New England town watching my five-year-old twin boys trying to master the basic movements of karate. It had been a gloomy day. Rain continued intermittently, and there was a storm in the air. I noticed there were several voice mails on my cell phone. That’s curious, I thought; I hadn’t felt it vibrate. I stepped into the foyer to retrieve the messages. The first one was from a good friend named Dave Henry, who was managing a considerable amount of money as chief investment officer of DKH Investments in Boston. “Harry,” his message said clearly, “Madoff is in federal custody for running a Ponzi scheme. He’s under arrest in New York. Call me.” My heart started racing. The second message was also from a close friend, Andre Mehta, a super-quant who is a managing director of alternative investments at Cambridge Associates, a consultant to pension plans and endowments. I could hear the excitement in Andre’s voice as he said, “You were right. The news is hitting. Madoff’s under arrest. It looks like he was running a huge Ponzi scheme. It’s all over Bloomberg. Call me and I’ll read it to you. Congratulations.”

I was staggered. For several years I’d been living under a death sentence, terrified that my pursuit of Madoff would put my family and me in jeopardy. Billions of dollars were at stake, and apparently some of that money belonged to the Russian mafia and the drug cartels — people who would kill to protect their investments. And I knew all about Peter Scannell, a Boston whistleblower who had been beaten nearly to death with a brick simply for complaining about a million-dollar market-timing scam. So I wouldn’t start my car without first checking under the chassis and in the wheel wells. At night I walked away from shadows and I slept with a loaded gun nearby; and suddenly, instantly and unexpectedly, it was over. Finally, it was over. They’d gotten Madoff. I raised my fist high in the air and screamed to myself, “Yes!” My family was safe. Then I collapsed over a wooden railing. I had to grab hold of it to prevent myself from falling. I could barely breathe. In less time than the snap of my fingers I had gone from being supercharged with energy to being completely drained.

The first thing I wanted to do was return those calls. I needed to know every detail. It was only when I tried to punch in the numbers that I discovered how badly my hand was shaking. I called Dave back and he told me that the media was reporting that Bernie Madoff had confessed to his two sons that his multibillion-dollar investment firm was a complete fraud. There were no investments, he had told them; there never had been. Instead, for more than two decades, he had been running the largest Ponzi scheme in history. His sons had immediately informed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and agents had shown up at Madoff’s apartment early that morning and arrested him. They’d taken him out in handcuffs. It looked like many thousands of people had lost billions of dollars.

It was exactly as I had warned the government of the United States approximately $55 billion earlier. And as I stood in the lobby of that dojo, my sense of relief was replaced by a new concern. The piles of documents I had in my possession would destroy reputations, end careers, and perhaps even bring down the entire Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the government’s Wall Street watchdog — unless, of course, the government got to those documents before I could get them published. I grabbed my kids and raced home.

My name is Harry Markopolos. It’s Greek. I’m a Chartered Financial Analyst and Certified Fraud Examiner, which makes me a proud Greek geek. And this, then, is the complete story of how my team failed to stop the greatest financial crime in history, Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme. For the previous nine years I had been working secretly with three highly motivated men who worked in various positions in the financial industry to bring the Bernie Madoff fraud to the attention of the SEC. We had invested countless hours and risked our lives, and had saved no one — although eventually, after Madoff’s collapse, we would succeed in exposing the SEC as one of this nation’s most incompetent financial regulators.

For example, it was well known that Madoff operated his legitimate broker-dealer business on the 18th and 19th floors of the Lipstick Building on New York’s East Side. But what was not generally known was that his money management company, the fraud, was located on the 17th floor of that building. Months after Madoff’s collapse, the FBI would reveal to my team that based on our 2005 submission providing evidence that Madoff was running a Ponzi scheme, the SEC finally launched an investigation — but that its crack investigative team during the two-year-long investigation “never even figured out there was a 17th floor.” I had provided all the evidence they needed to close down Madoff — and they couldn’t find an entire floor. Instead they issued three technical deficiency notices of minor violations to Madoff’s broker-dealer arm. Now, that really is setting a pretty low bar for other government agencies to beat. But sadly, all of this nation’s financial regulators — the Federal Reserve Bank, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Office of Thrift Supervision — are at best incompetent and at worst captive to the companies they are supposed to regulate. As I would later testify before Congress, “The SEC roars like a mouse and bites like a flea.” In retrospect, considering how much I have learned since then, and how much my team has learned, that probably was inaccurate: I was being too kind. Tens of thousands of lives have been changed forever because of the SEC’s failure. Countless people who relied on that agency for the promised protection have lost more than can ever be recovered. In some cases people lost everything they owned. And truthfully, the SEC didn’t even need to conduct an extensive investigation. My team had given them everything they needed. With the materials we submitted, it would have taken investigators no more than the time it took to ask Madoff three questions for his fraud to be discovered and his operation to be shut down. The magnitude of this Ponzi scheme is matched only by the willful blindness of the SEC to investigate Madoff.

Excerpted from “No One Would Listen,” by Harry Markopolos. Copyright (c) 2010, reprinted with permission from Wiley.

Source: http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/35606057/ns/today-today_books/

You can read a 10-year timeline at Amazon.com: No One Would Listen: A True Financial Thriller

Conclusions? Yes, you need to follow your compliance departments directives. No, your clients should not trust the government to protect their interests. And if any investment seems too good to be true, it probably is and you shouldn’t invest your clients money in it.

Advisor Marketing After the “Year of the Ponzi Scheme”

The Wall Street Journal called 2009, “The Year of the Ponzi Scheme.” Many people heard of the term “Ponzi Scheme” for the first time only because of the size of Bernard Madoff’s deal: $50 billion. Sadly with interest rates near zero, many retired people look at high returns delivered by such schemes and get sucked in with their life savings.

The Wall Street Journal called 2009, “The Year of the Ponzi Scheme.” Many people heard of the term “Ponzi Scheme” for the first time only because of the size of Bernard Madoff’s deal: $50 billion. Sadly with interest rates near zero, many retired people look at high returns delivered by such schemes and get sucked in with their life savings.

Someone commented on this with an article about a change in due dilegence. It suggests that financial advisors should investigate the ethics and integrity of the managers of recommended investments. Don’t just look at returns, look at WHO is generating those returns. Can this be done? Should you be held to this standard?

Time will tell if the Ponzi Schemes of 2009 lead to regulatory changes in 2010.

The Year of the Ponzi Scheme

If you weren’t familiar with the name “Ponzi” last year, you sure learned it quickly this year, along with the names “Madoff,” “Dreier,” “Petters,” and all the others who followed in the footsteps of the notorious fraudster Charles Ponzi.

That’s because, as the Associated Press reports, the number of Ponzi schemes that came to light in the U.S. has nearly quadrupled in the last year. The schemes, in which perpetrators lure investors with promises of high returns and use new investors’ cash to pay the old ones (and, of course, grab cash for themselves), topped 150 this year, compared to about 40 last year.

As a result, the AP says “tens of thousands of investors” lost more than $16.5 billion this year. That figure doesn’t include the $19.4 billion that Bernard Madoff is estimated to have bilked his investors out of in the largest Ponzi scheme ever, because Madoff was arrested in December 2008.

The AP’s review of federal and state criminal cases found that amid the recession and heightened public awareness of Ponzi schemes, the federal government stepped up its pursuit of suspected fraudsters. The Federal Bureau of Investigation launched more than 2,100 probes into securities fraud, up from last year’s 1,750 investigations, and it increased by one-third the number of agents working on high-yield investment fraud cases. And the Securities and Exchange Commission issued 82% more restraining orders and devoted more of its workload to investigating potential scams.

Source: http://blogs.wsj.com/bankruptcy/2009/12/29/the-year-of-the-ponzi-scheme/

NATIONAL BUSINESS MEDIA NOT COVERING TRUE REASONS FOR INVESTOR FRAUD SCANDALS

Dale Yeager a nationally known criminal analyst says that news coverage of the recent investor scandals is missing a critical aspect of these crimes. This overlooked issue is something Yeager calls the “Due Diligence Mess.”

Yeager, says the problem is the antiquated way due diligence is performed for investors.

“The financial crimes of the past year will continue to occur unless radical changes are made in the due diligence process,” states Yeager. “Due diligence must be performed as a criminal investigation not just a financial assessment.”

Based on his experience performing over 200 financial investigations, he believes that the focus must be on the ethics of the people operating the organization the investor will be placing their money into.

“Due diligence is about assessing a person’s credibility” states Yeager, “and people assessment has and always will be the domain of forensic psychology. Look at the amount of negative information that reporters have discovered about Madoff over the past few months. Information that provides a specific psychological profile of him, showing a lifelong pattern of narcissistic and unethical behavior.”

Yeager lays out a plan of action to prevent investor fraud with his article, “The Due Diligence Mess: 3 Reasons Why Ponzi Schemes and Investor Fraud Will Continue”.

“People have become accustom to using forensic accountants,” states Yeager. “But they need to become accustom to using that process in accessing behavior and personal ethics.

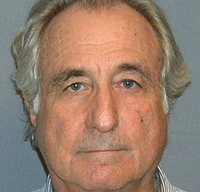

‘Evil’ Madoff Gets 150 Years in Epic Fraud

Victims Cheer Tough Sentence; Judge Slams Financier for Stonewalling Investigators; True Size of Losses Still a Mystery

[Richard: This Wall Street Journal article wonders whether wealthy families will flee money managers and just go to an index fund. Or if it will just blow over and be forgotten in 10 years. One reaction we can count on: regulatory compliance will get tightened once again.]

Bernard Madoff, the self-confessed author of the biggest financial swindle in history, was sentenced to the maximum 150 years behind bars for what his judge called an “extraordinarily evil” fraud that shook the nation’s faith in its financial and legal systems and took “a staggering toll” on rich and poor alike.

Bernard Madoff, the self-confessed author of the biggest financial swindle in history, was sentenced to the maximum 150 years behind bars for what his judge called an “extraordinarily evil” fraud that shook the nation’s faith in its financial and legal systems and took “a staggering toll” on rich and poor alike.

The landmark sentence, one of the stiffest ever given for a white-collar crime, came just six months after Mr. Madoff, a pioneer on Wall Street, allegedly told his sons that his entire business was a massive Ponzi scheme. The penalty sparked a burst of applause in a courtroom packed with victims of the fraud.

Earlier, nine of those victims confronted Mr. Madoff in court, calling him a “monster” and a “low life.”

“I hope his sentence is long enough so his jail cell will become his coffin,” said Michael Schwartz, 33 years old, of New Jersey, who said his family’s funds with Madoff had been for the care of his mentally disabled brother.

U.S. District Court Judge Denny Chin noted that more than 100 victims had written letters to him, citing one from a widow who said she went to see Mr. Madoff two weeks after the death of her husband, who had invested their life savings with him. Mr. Madoff put his arm around the widow and said, “Your money is safe with me,” according to the letter Judge Chin cited. Judge Chin said Mr. Madoff didn’t receive a single letter or statement of support before the sentencing.

Mr. Madoff, dressed in a charcoal gray suit and wearing rimless glasses, appeared without a single member of his family in attendance. He kept his back to the victims as they spoke. But for a brief moment during his remarks, he turned around to face them and said: “I’m sorry. I know that doesn’t help you.”

Mr. Madoff, 71, also told the court, “I will live with this pain, with this torment, for the rest of my life.”

While the trial phase of Mr. Madoff’s legal battle is ended, many questions remain unanswered. The public still doesn’t know the exact breadth of the losses and whether co-conspirators were involved. The case has also highlighted shortcomings of financial watchdogs, particularly the Securities and Exchange Commission, which failed to catch the crime despite repeated warnings.

Judge Chin faulted Mr. Madoff for failing to be more forthcoming with authorities since his Dec. 11 arrest. “I don’t get a sense that Mr. Madoff has done all he could, or told all that he knows,” the judge said.

During a short statement in court, Mr. Madoff spoke softly and pressed his hands against the defense table. He continued to insulate his family and co-workers, saying they were lied to. Family members who worked at the firm, as well as some employees, remain under scrutiny but haven’t been charged. He periodically drank water from a paper cup.

Following Bernie Madoff’s sentence of 150 years in prison, Kelsey Hubbard gets reactions from victims of the fraud and talks with WSJ’s Peter Lattman about what went on inside the courtroom.

“I cannot offer you an excuse for my behavior,” Mr. Madoff said. “How do you excuse betraying thousands of investors who entrusted me with their life savings? How do you excuse deceiving 200 employees who spent most of their working life with me? How do you excuse lying to a brother and two sons who spent their entire lives helping to build a successful business? How do you excuse lying to a wife who stood by you for 50 years?”

Mr. Madoff’s wife, Ruth Madoff, after the sentencing made her first public statement, saying that “like everyone else, I feel betrayed and confused. The man who committed this horrible fraud is not the man whom I have known for all these years.”

Mr. Madoff’s attorney, Ira Sorkin, said that Mr. Madoff was a “deeply flawed individual” but maintained that most of the fraud money went to other investors. He added that the $13 billion figure cited by the government as the net losses suffered by account holders since 1995 was overstated, since at least $1 billion in recovered assets will be returned to investors, and perhaps a lot more. The judge said that was irrelevant to the case. Mr. Sorkin said Mr. Madoff deserved only 12 years in prison, since he was 71 and had helped the government in its investigation — a statement Judge Chin questioned.

After the sentence, Mr. Sorkin said he hadn’t decided whether to appeal. “The judge has ruled,” he said. Because the sentence is within the federal sentencing guidelines for the case, which are advisory, few lawyers believe an appeals court would rule that it’s too high.

The sentence marked a victory for federal prosecutors who asked for the 150-year sentence, the statutory maximum for the 11 criminal counts he pled guilty to, citing the fraud’s size and duration. Mr. Madoff ran the Ponzi scheme for at least 20 years, prosecutors say.

It’s unclear where Mr. Madoff will do his time; the decision is made by the Bureau of Prisons. Mr. Sorkin asked for a medium-security prison in Otisville, N.Y., but Judge Chin said only that he would recommend to the bureau that it choose an appropriate facility in the Northeast.

Bureau of Prisons guidelines recommend a high-security prison facility for inmates serving sentences longer than 30 years. However, the bureau may still determine that a lower-security prison is appropriate.

There’s no parole in the federal system. Mr. Madoff is eligible for 15% off from his original sentence for good behavior, which would still leave him facing at least 127 years.

The sentencing, while high, isn’t a record for financial fraud. In the past decade there have been sentences as high as 330 and 845 years.

The case continues to reverberate on Wall Street. Michael Holland, chairman of Holland & Co., a New York investment company, says he thinks the Madoff case is one reason a number of investors, including wealthy families, endowments and charities, are moving from using a money manager to more “passive” investment strategies, such as index funds that track broad markets and leave less room for individuals to direct money.

“The future of the money-management business looks less rosy,” he says. “Years ago, people had to have their money managed somewhere, but today you may not be able to charge the large fees and live in Palm Beach to do it.”

But some are skeptical the impact from the Madoff case will be long lasting.

“Every time you get a bubble that bursts, scams come to light, but 10 years down the road we’ll be well past this, it will be ancient history,” says Bert Ely, a longtime banking consultant in Alexandria, Va. “There always will be new scammers and they won’t be dissuaded by this. He’s getting life in jail but look at all the great years he’s had.”

Source: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124604151653862301.html#